A Chemical Engineer and a Senator Walk into the Capitol

Why don’t the government’s policies fix gun violence? Illegal immigration? The exodus of businesses relocating to other countries? After all, we have the chance to elect 535 of the nation’s brightest minds to serve in Congress, and outfit them with staffs to help them process an incredible amount of information. Sometimes, all these smart people appear like “all the king’s horses and all the king’s men,” toiling but unable to put Humpty Dumpty back together.

Of course, such expectations of instant solutions are unrealistic. Our policymakers grapple with incredibly complex problems, where many causal relations form feedback loops that are not fully understood. Here I propose that our representatives take a cue from those who have made a science of analyzing complex systems in a way that allows them to understand causes of change and use that knowledge to accurately predict changes. The systems I refer to are chemical reactions – interactions of billions of atoms at the smallest scale that chemists and chemical engineers have learned to characterize simply enough that they can be studied and understood but not so simply that their models stray too far from reality.

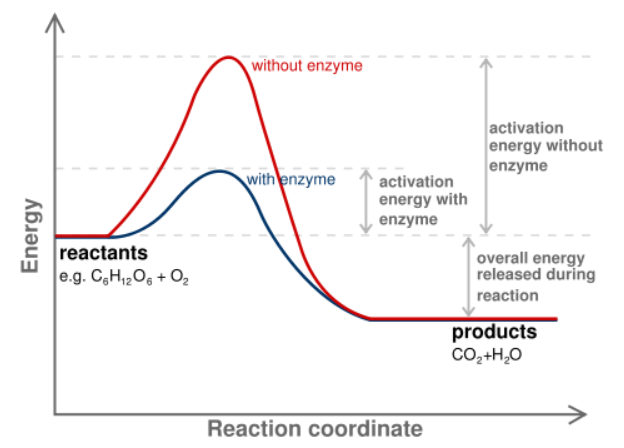

Much like economists and critics of abstract art, chemical engineers revel in looking at images of apparently arbitrarily intersecting lines and extracting meaning from them. The reaction coordinate, a type of graph pictured above, conveys two important thermodynamic parameters of a chemical reaction: the change in free energy and activation energy. In non-technical terms, these can be thought of as a system’s change in stability (more free energy means less stability) and its resistance to change (a higher activation energy means it is more difficult and slower to get the system to change). Understanding these parameters allows engineers to learn why reactions do or don’t proceed under given conditions. In the much less precise field of social and economic policy making, even experts often struggle to understand why a certain change in policy produces the effect that it does. While economics and social systems can never be reduced to two parameters, appropriating the thermodynamic concepts of stability and energy barriers can provide a sorely needed starting point to frame how our policies might achieve their desired effects.

Let’s explore what exactly we can learn from a chemical reaction’s activation energy and change in stability. A system where the products are much more stable than the original material (reactants) will, in the long run, convert all of the reactants to product. This is sometimes very quick to see, like a stove burner igniting butane gas. Sometimes, the “long run” is very long indeed – graphite is more stable than diamond at atmospheric pressure, but at everyday conditions it converts too slowly to observe. The difference? The second reaction has a much higher activation energy; its resistance to change is much greater. Adding more energy to the system, such as by keeping the diamond at 2,000 C, will increase the rate of change. Understanding these characteristics allow chemists and engineers to determine what reactions are important under what conditions and what different conditions could be set to achieve a desired outcome. For example, it allows us to discount the worry of diamond jewelry turning into graphite overnight under everyday conditions, while also offering a pathway (albeit under extreme conditions) to make that change, should we desire it.

Okay, why should legislators have these concepts in the back of their mind? Because chemistry is cool. More relevantly, I posit that legislation affects people’s actions through one of two means: Option 1 – changing the incentives and conditions to make an individual’s or organization’s situation after a given action more or less favorable, or option 2 – simply making the action easier or harder to accomplish. The first is analogous to changing the stability a system might reach, the second is parallel to raising or lowering the energy barriers to change. Examples of the first might be enacting financial incentives, such as tax breaks, for families whose children attend college, which would make pursuing higher education a more financially viable or “stable” course of action. An attempt to increase access to education using the second method might be allowing families freedom of choice among school districts or increasing distance learning options. (Side note: I would consider a tariff an example of option 1, decreasing the financial viability of importing goods, which may be confusing because we describe a tariff as a “barrier”, a word I have been associating with option 2).

An engineer would analyze if it is more important to consider a reaction’s change in stability or its activation energy, or if both must be carefully accounted for to accurately model the reaction. Likewise, understanding the primary reason(s) driving individual behavior and social trends is crucial to understanding how we can best change those behaviors and trends. Are citizens forgoing high school and college diplomas because they cannot afford the cost of schooling (including the opportunity cost of the wages they might be making while they are in class)? Or is it because there are no convenient means to access the education? Perhaps those who work struggle to find class schedules that accommodate their jobs. Of course, the answer is a blend, and the relative importance of these various factors vary from community to community. But asking these questions and beginning to learn the answers is a start to more effectively targeted and implemented policies.

Let’s look at what this lens might show us in a couple other examples. One application might be in predicting the effectiveness of efforts to reduce gun violence. Is the problem that over-availability of guns is making them more likely to be used in violent crimes or suicide? In that case, raising the barriers to access through “cool-down” periods, more stringent background checks, or more restrictions on the amounts and types of firearms available for sale may succeed in reducing the rate of violent gun crime in our society. On the other hand, if our communities create environments where members of society feel the need to arm themselves to feel safe or empowered, perhaps raising the barriers to gun access will only provide temporary or sporadic relief from the cycle of violence. Again, there is no universal answer. The crucial point is to stop assuming that Policy A or Policy B is The Answer to gun violence, and instead start to take a critical look at what factors drive people to seek out firearms and use them in anger.

This lens can also bring rational and analytical perspective to practices in society that tend to evoke heated rhetoric or emotional and poorly thought-out responses. One example is affirmative action policies. To some, they are a way to chip away at long-standing prejudices and discriminatory practices, allowing equal opportunity to all sectors of society. To others, they are an unwarranted leg up that in promoting one group, unfairly deny opportunity to others. The most pessimistic view is that such policies reinforce racist and prejudicial attitudes by suggesting that certain minority groups need preferential treatment to make up for a natural lack of ability. If we critically examine by what pathway affirmative action seeks to address unequal treatment, we can better understand which characterization of affirmative action is most accurate. The question to ask is, “does affirmative action lower the barriers to certain opportunities, does it seek to rectify the conditions in society that lead to unequal opportunities, or does it do both?” If it merely does the first, affirmative action may help individuals but does not set the conditions for long-term change. Even worse, it may indeed perpetuate stereotypes of a natural lack of ability. However, proponents of affirmative action point to potential long-term influences in attitudes that lead to empowerment of all groups. Seeing women or minorities in prominent positions in politics, business, and science, they argue, will inspire young women or other underrepresented youth to pursue similar ambitions. It can also discredit the view in society as a whole that certain groups don’t belong or cannot succeed in such positions of leadership. If this argument proves to be true, affirmative action may indeed be a potent driver of equal opportunity in the long run. While more data is needed on the topic, studies such as this one from Johns Hopkins show that having at least one black teacher correlated with increased likelihood of black students graduating high school and attending college; it is not unreasonable to suggest that a similar effect will stem from seeing minorities in other leadership roles. Either way, these are the questions that must be asked. Attacking – or defending – a policy such as affirmative action without critically examining by what mechanisms it functions will not lead us to better policy decisions and only further entrench the partisan differences that impede such progress.

Successful chemical engineers, entrepreneurs, and basketball coaches understand the importance of looking at data and trends rather than only trusting their emotions or unfounded opinions when making important decisions. This importance is even greater when determining policy that will affect thousands of people. Perhaps the sheer complexity and apparent unpredictability of society and economics intimidates decision-makers from taking a leap into the rational analysis necessary to design effective policy. But chemical reactions are complex too. We approach their analysis by looking at some fundamental parameters before diving into the details. In politics, our first step should also be analysis of fundamental qualities and causal relations in our society. Too often, our first step is to prove our opponent wrong or gain popularity. As long as that is true, we make impossible our own wishes to improve society and help others.

(By the way, Humpty Dumpty’s shattered configuration is way more thermodynamically stable. As a quick look at the reaction coordinate of putting him together would show, all the king’s horses and all the king’s men were fighting an uphill battle and never had a chance).

The Syntact Project

The Syntact Project